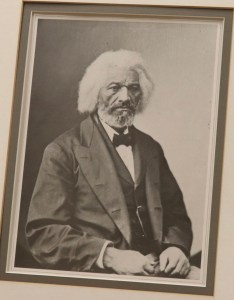

To ask who Frederick Douglass was would be perhaps to engage in intellectual or scholarly puerility. Yet it is a question that generates innumerable answers, while simultaneously it helps summarize the complex and simple, enigmatic and unequivocal character of Douglass. In a book, A Political Companion to Frederick Doulass, the authors write: “Douglass was a multifaceted and versatile thinker: theorist and practitioner, autobiographer and editor, abolitionist and statesman, orator and phenomenologist, romantic and realist, feminist and masculinist, assimilationist and decolonialist, moral suasionist and violent-resistance defender, Christian and critic of slaveholding Christianity, liberal and republican, law-breaker and constitutionalist, particularist and universalist, historicist and poeticist, a Marylander, a New Englander, a Rochesterian, a communitarian, a self-made man, a black man, a slave, a fugitive, an antiracist, an exslave.” Indeed, it would not be a sleight of hand or slip of tongue to refer to Douglass as the man and the myth.

But, maybe, the question can be framed or put in another way: Like Frederick Douglass himself who posed the question in what is inarguably his most famous oration: ‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?’, we too ask: What to the American republic was Frederick Douglass? First, for us Douglass was to America what Socrates was to Athens. Like Socrates, a gadfly, who philosophized in the hopes that his city, his land of birth, would become a model of the good or just life, Douglass thunderously clamored for America to cultivate its better angels. While Douglass was not a philosopher, he insisted on a return to the ideals which were the catalyst of the American Revolution, an epochal event which saw the birth of a new nation, breaking away from the colonial yoke of the British crown. In other words, he admonished the American national consciousness to wholly embrace universal ideas, such as freedom, liberty, justice and equality, all of which in principle are philosophical ideas or principles. While Douglass was never a philosopher in the actual sense of the word, he was a statesman, and by being a moral voice in a time of despicable vice, a time of moral decline, Douglass – like his fellow countryman Abraham Lincoln – embodies what we may call the “philosophic statesman”.

This brings us to the second point. We cannot talk about America without talking about Douglass, for since in talking about America, we talk about American statesmanship, political thought and its sordid history of slavery. This suggests we necessarily confront Douglass’s life. Why? Because Douglass sits in the highest rank of the pantheon of greatest American statesmen and political actors. One of the major events that continues to haunt the American narrative, or to paraphrase Douglass’ own words, the dark cloud which hovers above the horizon, i.e., American life, is the institution of slavery. Chattel slavery, if one were to be particularistic, left indelible footprints upon the American polity. It remains a scar on the conscience of American life. Few Americans understood the institution of slavery, few could speak of it with unrelenting vigor, and few were willing to give up their own life in order to put an end to it. That Douglass knew so well the implications of slavery owes much to his experience as a child born and bred in slavery.

“Douglass was six years old when, as an enslaved being, chattel, a person reduced to the category of thing, he was brought to Colonel Edward Lloyd’s plantation off the Wye River on Maryland’s Eastern Shore; he was eight when he was sent to Baltimore to live under the mastery of a slave holding couple; an unsweet sixteen when outsourced to the slave breaker Edward Covey; twenty when he escaped from Maryland as a fugitive, disguised as a sailor; twenty-three when he began speaking as a lecturer for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society under the influence of Garrisonian abolitionists.” (Note: He would eventually break away from Garrison).

Thus, Douglass was not a theoretician whose voice merely roams the corridors of history from a point of detachment. Douglass was himself a slave, and if indeed experience is the best teacher, who better can we look to than Douglass for the Black American perspective? To speak of the black perspective is to imply that this perspective is only a part of the whole, and to say that Douglass championed the black perspective is to infer that Douglass was a partisan. Certainly and in fact correctly, Douglass was deliberately and foremost a partisan. That is, he spoke for and defended the stance and responsibilities of a part, which is a very significant part of the American political whole.

But, by advocating for a part – the Black perspective – which had been ridiculed, condemned and reduced to nothing, Douglass only sought to complete the whole, or his only desire was to see that the whole is complete. This American whole, Douglass would suggest, is not perfect. But it can be made exceptional. (It must be noted here that it seems one of the greatest claims to statesmanship is wholeness, that is, bringing the body politic into a unified, monolithic whole is a defining character of the statesman. By preaching the message of unity and peaceful coexistence among his or her diverse subjects or fellow political denizens, it suggests that the wise statesman knows and understands the dangers of division and conflict, which affects not just a part but the whole of the polity, and thus, he must constantly steer the nation away from division to whole-ness or unity. Tied to the statesman’s message of unity or whole-ness is the message of hope and courage, especially during times of conflict and crisis).

Let us return to Douglass. By making the American political whole exceptional, Douglass did not embrace the simple notion of American exceptionalism, which holds that America is different from all other nations and therefore destined to play a greater role in the affairs of the world. Douglass knew all too well the sad and sorrowful spectacle of slavery that was unfolding right before his eyes, for he was from the very moment he was conceived bound to experience slavery. Thus, we think Douglass’ version of exceptionalism is rather aspirational, not accomplished, and it comes only with the latter Douglass, after his break from abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. The early Douglass, the Douglass who had to escape slavery, did not think for once that there was anything exceptional about America, American institutions or American heroes (the founding fathers). He thought they were all inhuman, unjust and an affront to both God and man. But the Douglass that we find in ‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July’, ‘The Freedmen’s Monument to Abraham Lincoln’ and ‘The Color Line’, this Douglass celebrated heroes, or more precisely, the American founding fathers. To be a hero, for Douglass, implies love of one’s country or fatherland, which hence implies love of freedom, equality and justice. This has the further implication that the hero would realize that all peoples, including his own people or race, are free and should be treated with dignity and respect and have access to equal opportunities.

This may be the reason why Douglass praised the father of the Haitian Revolution: “The countrymen of Toussaint L’Ouverture do not always stop to consider that his errors, if errors they were, should be regarded but as dust in the balance compared to the great services he rendered and the lustre he shed upon the character of their race” (Frederick Douglass on Toussaint L’Ouverture and Victor Schoelcher). Similarly, Douglass acknowledged Lincoln’s mistakes in The Freedmen’s Monument speech, noting above all that Lincoln “was a white man”. Yet, Douglass lavished praise on Lincoln as “an American great man” for his “vast, high, and preeminent services rendered to ourselves, to our race, to our country, and to the whole world.” In recognizing the exceptional deeds of the founding fathers in his Fourth of July speech, Douglass said: “They were peace men, but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men, but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew its limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny”. But Douglass added: “In their admiration of liberty, they lost sight of all other interests”. Taken in this sense then, the American founding fathers are true American heroes, by virtue of them creating the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. By doing this, the founding fathers gave hope to the American republic, hope that one day slavery would be completely vanished from the shores of America, and the ideas of equality, freedom and justice would be fully and truly realized. Thus, Douglass had to add that they lost sight of other interests, because slavery was alive and well at America’s founding and many decades after.

It follows that Douglass’ hero is the one who gives his people hope amid his mistakes, who calls his people to national renewal amid “the pitfalls in national consciousness”, to use Frantz Fanon. And if it happens that the hero achieves this, knowing that he might or even be killed in the process, Douglass would say he becomes the true hero. Douglass’ true hero would be Madison Washington, who – recognizes the dangers he would face – yet returns to free his wife or family from bondage (The Heroic Slave).

*Please reach out for more on what I take to be Douglass’ aspirational American exceptionalism.

(Black History Month Reflections)