What is the self? What does it mean for one to have a true sense of oneself? Is the self, or oneself or myself distinguished from other selves? These questions have pervaded human history and continue to dog the present state of the human condition. Throughout the ages, a myriad of pages and ink have been spilled on this subject of the concept of the self. Philosophers, scientists, historians, literary critics, anthropologists, classicists – in a word, all the thinkers who have engaged with and developed theories about the human condition – all seek to investigate and give a full account of the individual and her relation to others. In an attempt to respond to these questions, we turn to Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Note: We use ‘self’, ‘man’, or ‘individual’ interchangeably. ‘Man’ here by no means implies gender specificity, although Emerson – given his era – seems to use it to refer to the individual man qua man).

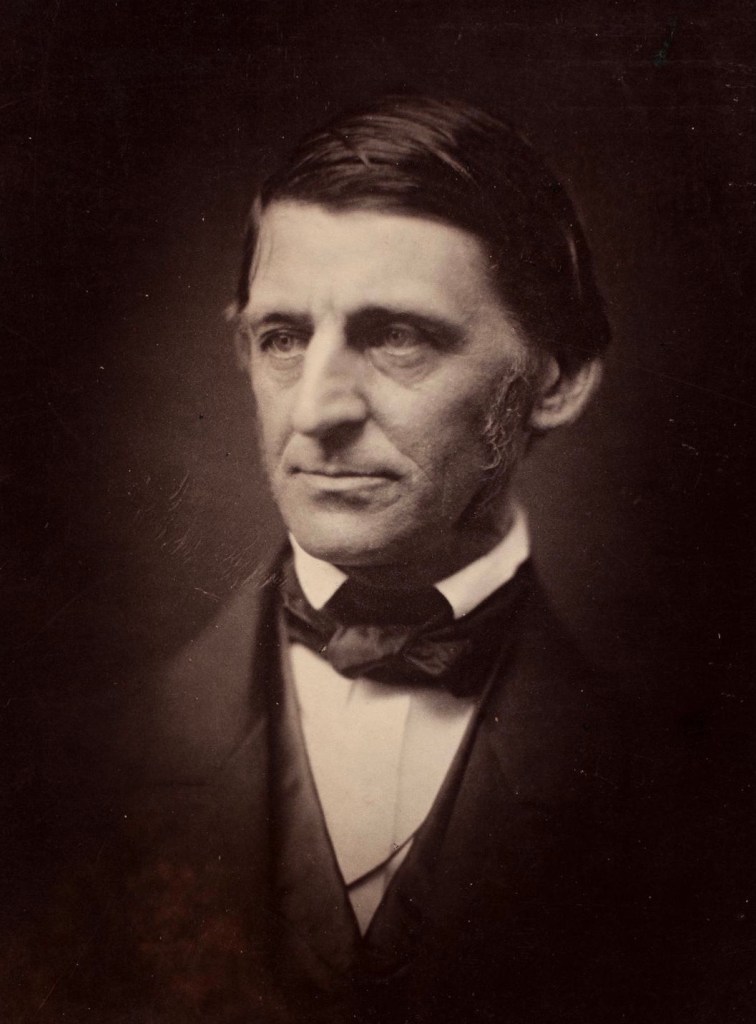

The place of Emerson in American letters remains but a conundrum among scholars and thinkers. Even his ephebes are in a constant state of agon regarding whether Emerson is on the one hand, an experimental critic and essayist, and on the other hand a Transcendental philosopher. Some, including Harold Bloom, contend that the latter view must be negated, that Emerson is not and has never been a philosopher. Others, like Stanley Cavell, insist – and I think rightfully so – that Emerson is both a philosophic genius and a literary paragon. Whether one agrees more with Bloom or Stanley, what remains indisputable and incontestable is that Emerson is “the mind of our climate” as Bloom puts it (The American Canon, p. 13). What Bloom means by this is that Emerson is the principal source and supreme commander of American intellectual life. (Here, we approach Emerson from an apolitical, non-nationalistic stance, since we believe his ideas to be universal and accessible to all, not only the American individual).

Because Emerson is the mind of the climate, he is thus the climate, and if he is the climate itself, whatever happens within the climate is simply subsumed under it. Paraphrasing Bloom as he notes elsewhere, if others like Thoreau, Whitman, Dickinson, Stevens, and T. S. Eliot wrote the climate, that climate is Emerson. Bloom is then right when he says: “If a single American has incarnated our daemon, it is Emerson, not our greatest writer but merely our only inescapable one” (ibid p.35). One cannot avoid Emerson, for the one who studies literature, especially American literature, always finds herself confronting Emerson, either as a critic or as a fan. Thus, we can even say that Emerson is like the self, since one cannot escape from or avoid oneself, for ‘self’ constitutes inner being. Self is the metaphysical essence which underlies the individual, for without self, there is no individual or personhood. To use Kantian language, the self is ‘transcendental’. This is all the more appealing since Emerson is the writer of the self, hence his doctrine of the ‘divine-man’ (Divinity School Address) or ‘self-Reliance’ (Self-Reliance).

In his DSA address, Emerson boldly proclaims: “Yourself a newborn bard of the Holy Ghost, cast behind you all conformity, and acquaint men at first hand with Deity.” Elsewhere, in The American Scholar address, he declares: “Man Thinking must not be subdued by his instruments. Books are for the scholar’s idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men’s transcripts of their reading”, and speaking further of histories or historical books especially, Emerson adds: “They pin me down. They look backward and not forward. But genius looks forward: the eyes of man are set in his forehead, not in his hind-head: man hopes, genius creates”.

Emerson is at his most rebellious in the above passages. The two addresses mark the beginning of what was to become a tumultuous quest for the new kind of self or man, something which led religious America to declare him a heretic. Emerson here introduces his notion of self-reliance, and thus, the addresses premonish and precede of his more radical essay, Self-Reliance, in which he elucidates entirely his doctrine of the self-reliant individual, the anti-conformist, the stubborn species who must oppose society and its vortex of shifting opinions.

But before Emerson’s Man Thinking becomes self-reliant, he must at first realize and then attain a sense of self or inner being that is simultaneously divine and human. As a “newborn bard of the Holy Ghost”, man no longer needs to look to the past, to the historical Jesus. For Emerson, the story of Jesus as portrayed by Christianity creates in men a feeling of alienation. The traditional account says Jesus died for every man’s sins, that Jesus’ actions remain at the apotheosis of what the individual man can do. But Emerson disagrees, he thinks that Jesus ought not to be the only or final example to mankind. In other words, Jesus’ decision to accept crucifixion should not be the limit of man’s potential. Emerson suggests that within the individual self, within man’s inner being, lies all the qualities that Jesus possessed. For Emerson, man is a potentiality waiting to be an actuality. But this actuality is being hindered by religious beliefs which insist that man is limited, that he is naturally confronted with limitations which he cannot supersede. For the individual to realize his fullest potential, to be his true self, he must abandon such conformist views, he must get acquainted with Deity, he must recognize that God is in him. In a way, then, man’s self is God. Man is God not in the sense that he is the all-powerful, all-knowing Creator of the universe as Christianity decrees. Man is God, or rather God-like, when he can live up to his instincts, when he embraces spontaneity, just as when God instinctively, or rather spontaneously, without any prior plans, decreed, “Let there be light” (Gen 1:3). Like God who creates, man is the genius who creates and must create.

Since Emerson claims that man needs not look to the alienating story of the historical Jesus and historical Christianity, Emerson therefore condemns the past, convinced that we cannot look to past historical events for inspiration. Historical events, for Emerson, are musings of the minds of men. History is nothing but what man writes or records, but man writes about things or events that stand in relation to the conditions or situations of his times. This implies that man’s history is merely a history of his own state, which is ephemeral. Emerson, thus, contends that since men live in historical epochs that are but fleeting moments, the events or people of the past cannot inspire present conditions and people. The past is no compass for the present, let alone the future. Because past events were the makings of men who lived in the past, therefore, present or future events ought to be made by present or future men. Here, it is clear Emerson is deeply anti-historicist. Yet, his anti-historicism is a kind of historicism. In urging individuals to focus on the challenges of the current moment (the present) and to realize themselves within that moment, Emerson implies that individuals live within given contexts. These contexts, I contend, are necessarily historical, since they have their own set of issues which preoccupy individuals or selves. Thus, while Emerson criticizes past history, he embraces present, and hence, future history.

Furthermore, Emerson’s critique of history and the historical Jesus implies a critique of books, including the Christian Bible. The only source, i.e., historical source, for the life of Jesus is the Bible, and, like it, all books written by men are responses to given historical modes. In other words, books recount events and ideas from the past, or which were done and written by men who lived in the past. Since Emerson condemns the past, he must necessarily be implying a condemnation of books: “Books are for the scholar’s idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men’s transcripts of their reading” (TAS). However, Emerson’s polemics against books is only implicit in his condemnation of men who look to other men, long past and dead, for inspiration. Thus, it suggests that Emerson does not hold books in contempt, for if he does, it would be folly and hence would contradict his own intellectual project. What Emerson seems to be suggesting then is that the present man must write his own books or rules. That is, he must carry out deeds that enable him to realize and exercise his inner being. Man ought to be self-reliant because he has access to his Self or to God. Man should not look to books, including the Bible for inspiration, for this shows and tells man that he is a limited being. Man must search within himself for meaning. This is what it means for man to be his true self, his true essence. This is what it means for man to be able to directly read or have access to God. Thus, Emerson claims that the search for self is not external, i.e., not in books or in other individuals. The self can be found only internally, that is, by looking inward.

Notes/Further Readings:

* These reflections are dedicated to Zoe M, who got me thinking about Jesus and the concept of selfhood. I must state unequivocally that I by no means take a side nor endorse Emerson’s views on Jesus. I simply find it a worthwhile exercise to engage with his writing. In the next piece, I will explore Jesus from both a historical and transcendental (philosophical or conceptual) perspective in the work of the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel.

DSA – The Divinity School Address

SR – Self-Reliance

TAC – The American Canon

TAS – The American Scholar