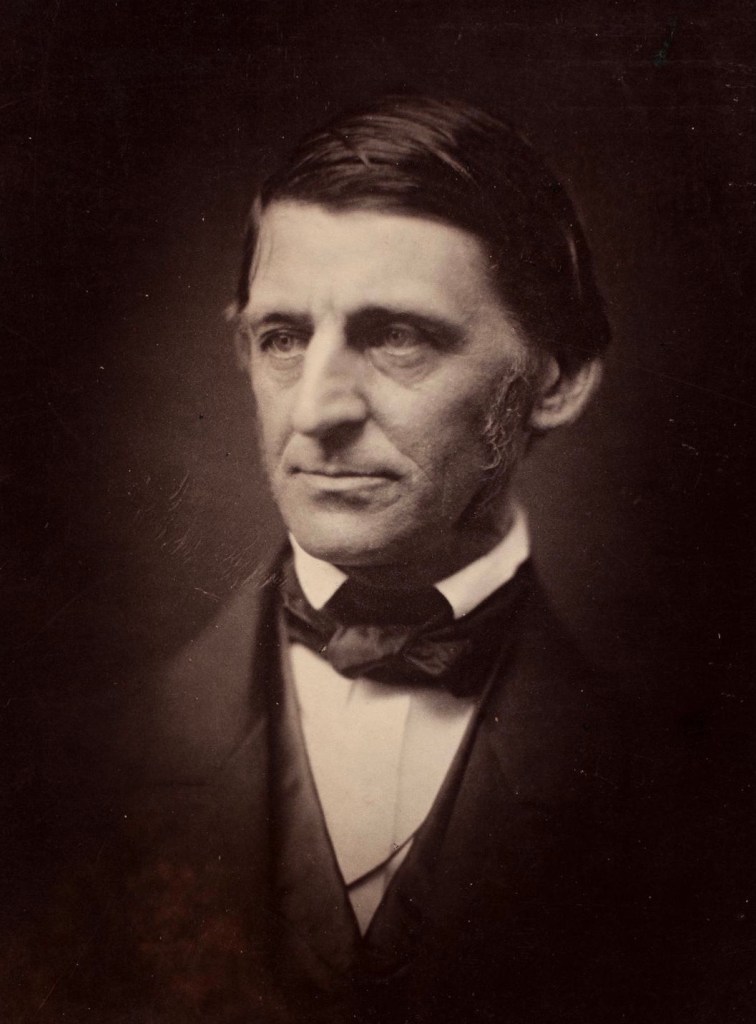

Who was Ralph Waldo Emerson? Some would contend that he was never a philosopher, since in some of his writings he is very critical of philosophy, for he declares in his essay Experience that “Life is not dialectics… Life is not intellectual or critical, but sturdy.” Others might suggest that he was a poet, since he wrote a few poems; or an essayist, since his major works are essays, that is, written in prose. Perhaps, we should call him an idealist or a post-idealist given his emphasis on the ability of the mind or the soul to transcend a given historical mode; or a pragmatist, owing to his staunch defense of what he calls “Man-Thinking” (The American Scholar), or the individual’s ability to use thought as a mode for action or responding to the problems and demands of the real world; or even a political radical, due to his polemics against conformism (Self-Reliance) – in other words, his insistence that the individual must and should not sheepishly follow the herd.

Whatever disagreements may arise over how to describe Emerson’s intellectual identity, one central fact is constant across his intellectual project: he sees nature and the human mind as the fundamental forces of objective reality. He is a primary, in fact the primary champion for man’s or the mind’s exploration of nature, something that would lead to a unity between the individual and nature. For Emerson, nature and mind are not two poles – negative and positive – standing in sharp contrast to one another. Before Emerson’s birth and in the era that marked his meteoric rise to intellectual stardom, philosophers, artists, and poets – in other words, the major thinkers – were preoccupied with questions about nature (the objective world or reality), and the mind (the subject that perceives reality).

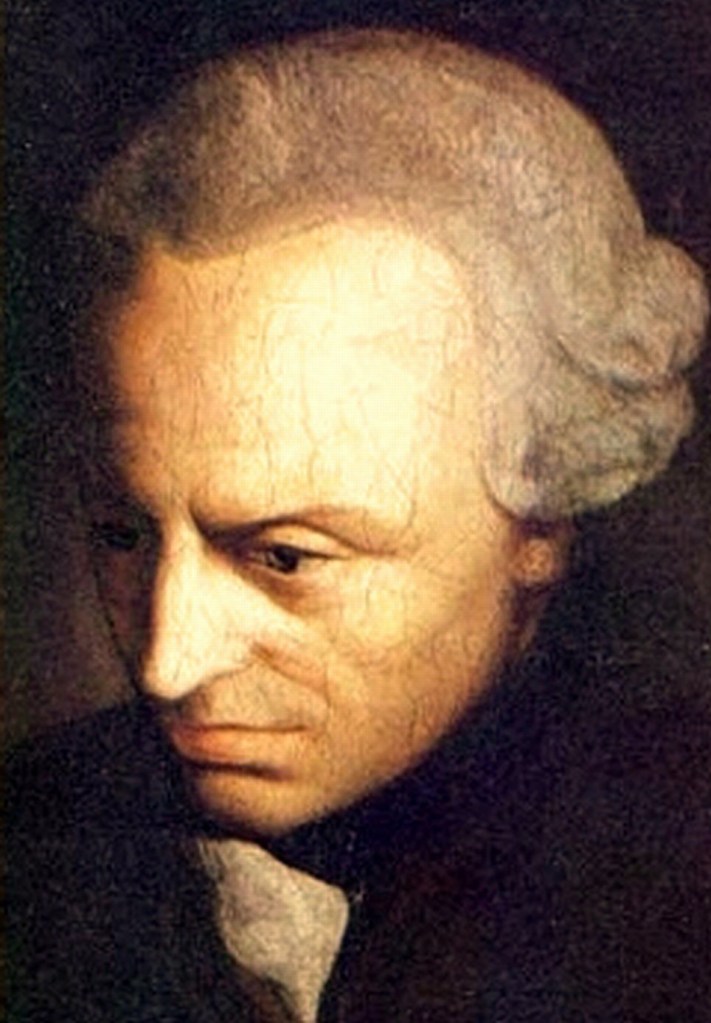

Some, including Immanuel Kant, who, by way of Coleridge, influenced Emerson, argued that the objective world or the world of reality cannot be known in the absolute sense. We cannot know or have knowledge of things-in-themselves, or noumena. But a subject, Kant claims, can have knowledge of things-as-they-appear to the senses. Kant calls such things or objects, phenomena. Furthermore, Kant says we can only ever describe the natural world, or distinguish subjective perceptions from objective representations (reality), through a priori categories, i.e., pure concepts which are intuitively known by the mind or subject by way of the faculty of the understanding. Thus, when the mind or subject confronts objective reality, it comes with concepts that are necessary for experience, and hence relies on categories (cause and effect, inference and subsistence, necessity and contingency), which are the conditions for the possibility of objects and objective experience in general.

Although Kant claims that our experience of the objective world is governed by natural laws, his distinction between noumena and phenomena and his claim about the impossibility of knowledge of the former suggest that the human subject cannot fully grasp objective reality or nature. In a way, Kant and his followers seem to be proposing a stark dichotomy, an unresolvable separation between what the mind claims to know and what the thing actually is, independent of the mind perceiving, sensing or knowing it.

Following in the footsteps of Kant, G. W. F. Hegel partially accepts the distinction between noumena and phenomena, between what is implicit (an sich) and what is explicit (für sich). However, unlike Kant, Hegel says we can have absolute knowledge of the thing-in-itself. For Hegel, the distinction Kant makes between things-in-themselves and things-as-they-appear brings about the distinction, even the opposition, between subject and object, precludes the possibility of absolute knowledge. He disagrees with Kant that we cannot have absolute knowledge.

In the Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel examines the shapes of consciousness and the shapes of spirit to show how we can come to absolute knowledge. (Hegel’s notion of Spirit has been interpreted in various ways, but I treat it here as the individual who knows or perceives the object, i.e., the subject). At the end of this examination, the opposition which exists between subject and object disappears, and the subject comes to know absolutely that the object that she perceives is part of herself. (Since Hegel has the notion of objective Spirit in mind, which is the unity of individual subjects and the objective, real world; thus, the subject and object seem to have an underlying identity: both exist as Spirit). Absolute knowledge, for Hegel, is the final unity of subject and world (object). To know absolutely is to grasp the nature of things. Absolute knowledge is when the subject goes beyond itself, becomes an object or is against itself as object, and then returns to unity with itself. Yet, within this unity, the subject or Spirit (Geist) can still distinguish or separate itself from the world or object. At a higher level of the dialectic, i.e. in Absolute Knowledge, this separation involves no opposition because the subject sees and knows the object as merely an extension of itself.

By claiming that a dichotomy between or separation of subject and object exists, Kant concludes that absolute knowledge is impossible, whereas Hegel says that the separation should not and does not prevent absolute knowledge. In fact, Hegel suggests that the separation is simply a proof and a necessity for a subject to have absolute knowledge. Thus, while Kant does not resolve the epistemic problem, Hegel resolves it, viz., that we can have absolute knowledge.

For Emerson, there is no dichotomy or separation, and hence, no epistemic problem at all. He wants to show that the mind and nature are not separate and opposed to each other; that they are in fact joined together, that ‘the mind is nature and nature is mind’. The division of knowledge into knowledge of the thing- or nature-in-itself on the one hand, and knowledge of only appearances on the other, arises from a belief that the thing-in-itself, i.e. world or nature, is distinct from the mind, or subject. Thus, this distinction prompts the question of whether absolute knowledge is possible. To avoid this, Emerson suggests that the objective or natural world is knowable and accessible to the mind, and thus it requires no dialectic or opposition to reach there. Therefore, between Kant and Hegel – both of whom accept the separation of subject and object – stands Emerson, who seems to suggest that the distinction is superficial and therefore unnecessary. What is Emerson’s conception of nature and mind?

A common thread throughout all of Emerson’s works is the idea that nature is supreme; that nature is, ever was, and ever will be. Unlike some of his contemporaries and intellectual equals who claim that history is the force that drives human progress or that the state, polis, or community is what determines our lives, Emerson sees nature as the basis of everything there is: “Nature… refers to essences unchanged by man; space, the air, the river, the leaf” (Introduction, Nature)1. For Emerson, nature is all around us. It is the ground on which we walk, the air we breathe, the water we drink, the plants we eat, the source of raw materials, with which we build. In other words, nature makes life delightful, and this delight is only possible because the mind works on nature, i.e. man shapes natural objects according to his will. Simply put, delight does not produce itself. It is brought about by the intellect or mind, for Emerson says that “the power to produce this delight, does not reside in nature, but in man, or in a harmony of both” (Nature), and that “the world is not the product of manifold power, but of one will, of one mind; and that one mind is everywhere active” (Divinity School Address). In this passage, we find Emerson at his most pragmatic: the active mind or man is what shapes nature, or whom nature “elicits”. The individual is not just a passive being, who relishes the beautiful things she finds in nature. Her pleasures are only satisfied only if she takes nature to be for her.

In the previous passage, however, Emerson seems to be suggesting a distinction between mind (man) and nature, since “harmony of both” implies an earlier disharmony, that the two are being brought together. This is, of course, the case, for Emerson does not deny that the mind and nature exist separately. Yet, their separation, I contest, can only be called a superfluous separation, i.e. one that can be – to use Hegelian language – superseded or overcome (“Aufhebung”). The overcoming of this dichotomy occurs when “all natural objects make a kindred impression, when the mind is open to their influence” (Chapter 1, Nature).

For Emerson, the mind is most complete when it is in nature, when man finds inner joy in what impresses him, when the natural world gives him joy and calmness to sooth his internal grief: “The lover of nature is he whose inward and outward senses are still truly adjusted to each other” (ibid). In other words, when the thing-in-itself and the thing-for-others, or the world of appearance, are aligned in such a way that produces a melody of harmony, what is implicit in nature becomes explicit through the mind’s action or its shaping of nature––as Coleridge puts it, “Esemplastic”.2

In speaking of nature in the philosophical sense, Emerson claims that the universe comprises “Nature and the Soul”, the soul being the mind or consciousness. Emerson distinguishes the soul from nature, but gives two different accounts of nature. “Strictly speaking, therefore, all that is separate from us, all which philosophy distinguishes as the NOT ME, that is, both nature and art, all other men and my own body, must be ranked under this name, NATURE. In enumerating the values of nature and casting up their sum, I shall use the word in both senses” (Nature). The first conception of nature is nature taken as consisting of all that the individual is not, for example, the sun, air, mountains, flowers, woods, etc., and the second conception includes other persons and the individual’s own body. Thus, Emerson’s very broad meaning of nature is that it consists of nature (in the sense of the world of things or objects), art, other individuals and one’s own body. We can now say, ‘I am nature, nature is me’. Furthermore, Emerson says: “In the woods, we return to reason and faith”. This implies that out of nature, man is without reason or he lacks the capacity to make rational decisions, and he has no faith, i.e., he thinks himself unable to be the master of his destiny. Because the individual is without reason and faith outside nature, he is incomplete. To be whole, he must return to nature.

Now, we have mentioned that for Emerson nature is the fundamental reality. This generates a contradiction: if nature is all around us, does the individual have to retire into the ‘woods’ to be rational? Isn’t he already in nature given that all around him, there is the sun, air, and water? Emerson’s use of “woods” is to emphasize the individual’s complete absorption into nature, since it is in the woods that we most concentrate on that which is immediate or before us. It follows that there we immediately become rational, and hence, are able to distinguish among things in the natural world. Better put, there is immediate knowing or immediate knowledge in Emerson, as in Hegel.

In the Divinity School Address, Emerson says that in nature, an “overpowering beauty appears to man when his… mind open[s] to the sentiment of virtue. Then he is instructed in what is above him. He learns that his being is without bound; that, to the good, to the perfect, he is born, low as he now lies in evil and wickedness” and he adds “The intuition of the moral sentiment is an insight of the perfection of the laws of the soul”. These passages suggest that Emerson views nature as the source of immediate knowledge. Man comes to know of virtue, of good and evil, of perfection and imperfection, when he immerses himself wholly in nature. From this immediacy, too, are laws which tell him “He ought”, or which aid him in leading a virtuous and delightful life, because “in the soul of man there is a justice whose retributions are instant and entire”.

However, let us return to Emerson’s assertion that the “universe is composed of Nature and the Soul” (Intro., Nature). It contains an important ambiguity. He claims that the universe consists of nature and the soul, and the soul is nothing other than the mind or consciousness, not some foreign or alien entity. The ambiguity consists in the claim we made earlier that Emerson seeks to prove that nature and mind are the same, or that nature is mind and mind is nature. If this is so, one may object: why then is the universe made up of two entities – nature and soul or mind – instead of one: nature? However, just because we argue that mind and nature are similar or joined does not mean they have to be the same. Nonetheless, they are not separate. The mind or soul is within nature, and whatever is within something else is part of that thing which contains it. Thus, the soul or mind is part of nature, and therefore, is nature.

But since there is another sense in which nature includes everything that is “NOT ME”, in other words, that is not mind or soul, it seems soul or mind must have a sort of independent, yet un-superseded existence. Such existence can be superseded only when the soul or mind is understood to be existing in a unity with everything else that comprises nature. This implies that the soul or mind exists for as long as nature does: “Him nature solicits with all her placid, all her monitory pictures; him the past instructs; him the future invites” and “The next great influence into the spirit of the scholar, is, the mind of the past” (The American Scholar). These passages suggest that Emerson views nature as an unbounded reality, existing beyond any historical epoch. To this extent, spirit, soul or mind is ahistorical, i.e. it goes beyond any given historical reality. Though one can say ‘there is spirit of the age’ – or to use Hegel’s term “Volksgeist”* (spirit of a/the people) – this only suggests that soul, mind, or spirit can reside within a given era and can be reflected in its social and political laws and institutions, all of which are products of the human mind: “The ambitious soul sits down before each refractory fact; one after another, reduces all strange constitutions, all new powers, to their class and their law” and it is “a law which is also a law of the human mind” (ibid). Thus, nature and soul/mind/spirit, for Emerson, cannot be located within history, and hence the unity of the two can best be seen or expressed in the fact that they extend beyond any notion of time.3

Notes:

(1) In this essay, I cite the longer essay Nature, which is considered Emerson’s textbook on nature, as opposed to the shorter essay Nature, which is part of the Second Series.

(2) “Esemplastic” is a term which Samuel Taylor Coleridge introduces in his Biographia Literaria. It has been interpreted as “to shape into”. He uses the term to refer to unity of object, or the unifying power of the imagination. In this sense, Coleridge’s “Esemplastic” resembles Kant’s schematism.

(3) But whereas Hegel sees Spirit as having a historical determination towards absolute knowledge, Emerson does not. While Hegel is a historicist, Emerson is an anti-historicist. (For more on Emerson’s anti-historicism: David K. Hecker’s “Nature Will Not Be Disposed of”: Emerson against Historicism)

Further Reading:

Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason: trans. & ed. by Paul Guyer & Allen W. Wood. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant, Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. translated by A. V. Miller: Oxford University Press, 1977.

*For more on “Volksgeist”, see Michael Inwood’s A Hegel Dictionary